Intentional is a gameplan...

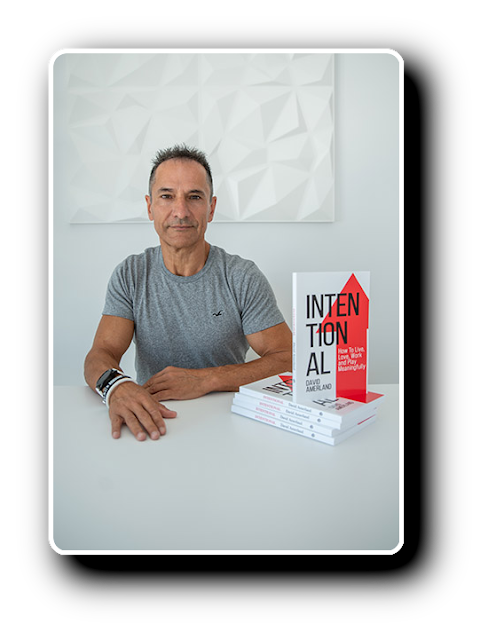

By David Amerland

INTENTIONAL: HOW TO LIVE, LOVE, WORK AND PLAY MEANINGFULLY, Nonfiction, NewLine Books, 218 pp.

Live your life the way you want to. Manage stress better. Be more resilient and enjoy meaningful relationships and better health. We all want that. Such life leads to better choices, better jobs, loving romantic partners, more rewarding careers and decisions that are fully aligned with our aims.

What stops us from getting all that is the complexity of our brain and the complicated way in which the external world comes together. The misalignment between the internal states we experience and the external circumstances we encounter often leads to confusion, a lack of clarity in our thinking and actions that are not consistent with our professed values.

Intentional is a gameplan. It helps us connect the pieces of our mind to the pieces of our life. It shows us how to map what we feel to what has caused those feelings. It helps us understand what affects us and what effects it has on us. It makes it possible for us to determine what we want, why we want it and what we need to do to get it.

When we know what to do, we know how to behave. When we know how to behave we know how to act. When we know how to act, we know how to live. Our actions, each day, become our lives. Drawn from the latest research from the fields of neuroscience, behavioral and social psychology and evolutionary anthropology, Intentional shows how to add meaning to our actions and lead a meaningful, happier, more fulfilling life on our terms.

There is little point in trying to define what ‘life’ is. Philosophers and,

surprisingly, even some biologists, have never agreed on it.

Biology however tells us that life is: “defined as any system capable of

performing functions such as eating, metabolizing, excreting, breathing,

moving, growing, reproducing, and responding to external stimuli.”

The moment you think about this definition you know that there is little

point in trying to adapt it to concepts such as “living a good life” or “a life

well-lived”, yet it is by those that most of us intuitively try to measure and

understand what it is we mean when we mention “life”.

As it happens I will give you a much better definition but before I do I

will start with an obvious truth: we all struggle with the exact same thing

that is, knowing how to behave.

In trying to live a life, good or bad, we all seek to find, discover or accept

a set of rules that basically tell us how to behave in any given situation.

When we accept social mores, religion, the law, tradition, culture, a code of

conduct, a belief or an ideal what we basically engage in is a direct attempt

to find our personal rule book that tells us exactly what to do when we need

it.

I am a sucker for mindless action flicks that spike my adrenaline levels and

shower me with eye-candy special effects. If you’ve never seen Wanted,

starring Angelina Jolie, James McAvoy and Morgan Freeman, then I strongly

recommend it, not least because in one of his over-the- top cinematic speeches

delivered with that all-too-familiar authoritative deep, tonal voice Freeman’s

character declares:

“Insanity is wasting your life as a nothing when you have the blood

of a killer flowing in your veins. Insanity is being shat on, beat down,

coasting through life in a miserable existence when you have a

caged lion locked inside and a key to release it.”

He goes on to give the requited spiel about a fraternity of super- assassins

that take it upon themselves to guide history by killing selected people “for

the greater good” and he finishes it with the memorable line: “This is what has

been missing from your life Wesley: Purpose.” I did say it’s over-the-top. At

the same time the speech has a point. A life lived without a purpose is a life

mostly wasted. And purpose is frequently defined by knowing what we should do

and being actively engaged in doing it.

Whether we realize it or not, we all feel the need for this kind of guidance

that gives us a deep sense of purpose. Because we are born physically helpless

we have evolved to latch onto and work hard to understand our immediate

environment and the people around us. This makes us, as we grow older,

intensely pro-social. At the same time it provides us with a ready-made set of

expectations, rules and guidelines to guide our behavior that arise from the

collective behavior of those around us.

That behavior is the culture we experience and the traditions we abide by.

The problem with this is that rather than defining for ourselves what is

important to us we accept that which is given to us. That which is given to us

is rarely what we want, but it can very easily become what we settle for.

Settling is an evolutionary-programmed trait. Let me explain: Life is hard.

It really is. Even if we happen to have the extraordinary luck to be born into

a very rich family whose legacy gives us everything we need to live comfortably

for the rest of our life, maintaining that fortune and navigating through life

is going to be fraught with risks, traps and constant upheavals.

We need other people. Other people need us. That is a truth. But the reasons

for this mutual need are usually contradictory or, at the very least,

sufficiently at odds with each other to make trust an issue and turn cooperation

into a risk-assessment exercise.

All of this takes inner resources. It takes attention, thinking, planning,

mental and psychological effort, perhaps some introspection. It frequently is

emotionally painful and psychologically costly. We are programmed to avoid it

because it adds to the intrinsic difficulty that is life.

If you want the definition of life here it is: It is a game plan that emerges

from the collective activities for survival of everyone around you. That is,

everyone. It is difficult because it is unpredictable. It is unpredictable

because no one knows the rules. In an emergent game plan things change

spontaneously according to the same principle that guides us to settle for what

we are given: conservation of energy. When ‘witches’ threaten our communal

beliefs, the stability of our governing institutions and the perceived natural

order of the Cosmos it is required of us to hunt them down and publicly burn

them.

The act, however, barbaric, painful and seemingly inhuman restores the perceived

natural order of things, reinforces the power of our institutions to safeguard

our way of life and impresses upon us the value and desirability of accepting

what we are given. Life goes on much easier then.

When the public burning of witches however marks our way of life as brutal,

our religious leaders as misguided, fanatical zealots whose actions endanger us

all and our institutions as unbending, power- hungry instruments of control, we

become more enlightened. More accepting. Our society becomes tolerant. Our

horizons broader. Life goes on much easier then.

“Easier” is what we have been programmed to seek because it increases the

chances of our survival. What made sense in pre-historic times when the outside

world could easily kill us has, in our days, evolved into a complex dance of

what we believe and what we reject, what we accept and what we actively seek.

We have created a world that pretty much guarantees our survival. Yet, for most

of us that is no longer enough.

We lack the deeper sense of purpose that makes us feel truly alive. We have

the key to releasing the “lion” inside each of us but choose not to use it.

This makes our life a complex weave of small advances and retreats. Victories

and losses that are designed to keep us in place until we no longer care and it

no longer matters.

I say “designed” when I describe the constant churn of victories and losses

that are life, but that is a mislabel. Life is a system. Like any system it seeks

stability in order to function. Stability demands conformity. Almost like a

biological organism, the system that we call “life” rewards innovation and

change (i.e. mutations) sufficiently to progress but makes it hard enough for

them to become established so that it is never severely disrupted.

It is no accident that in our lifetime we shall each experience only one

great innovation or upheaval. More than that and it may truly be the end of the

line for the experiment called “Human life on Earth”.

This need to live by choosing “the path of least resistance” because it

allows us to use the least amount of energy to coast through life leads to some

pretty convoluted mental acrobatics. We are, for instance, perfectly at ease

with a Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde transformation where we present a different face

(and maybe, even values) to those we work with and a completely different set

of behaviors to those at home or our friends at the pub.

We can use ‘morality’ to ostracize and dehumanize fellow human beings who are

different from us, because their existence creates perturbations in the social

system we directly experience that require greater energy in order to deal with

and may, even, challenge our own sense of right and wrong with our own life

choices.

The ease with which we can turn on anyone not of our own religion, social

caste, skin colour, ethnicity, neighbourhood or area is testament to this.

History supplies a long list of such instances that range from the destruction

of Carthage in pre-history to the genocides that took place in Rwanda and

Bosnia in the closing years of the last century.

In each case the ingredients are the same incendiary mix of social stress,

political polarization and a dehumanization of the ‘other’ that is different,

strange, outside our own group and therefore the enemy who deserves to be eradicated.

The irony that this is the same game only with different players escapes its

participants who had they been capable of such awareness would have behaved

differently anyway. The irony is rich here because in order for this game of

life called “division” and “ostracism” to work its players must be capable of

exhibiting the same behavior when confronted with the same set of

circumstances. The oppressed turn oppressors just as easily as the victims can

turn into aggressors. Given similar circumstances and capabilities we are

usually pretty good at coming up with justification of our behavior and if you

need a living, breathing example of such role reversal look at the atrocities,

injustice and demonization of the ‘other’ carried out by none others than the

Israelis upon the Palestinians.

A case of role-reversal, where those who history has frequently ascribed the

role of victims turn into aggressors and perpetrate on their neighbors the same

type of persecution they have, historically, experienced themselves.

Now that we’ve established, on these broad lines, that life is a game whose

rules are the same everywhere and we have seen, again broadly, how similar

circumstances allows us to behave in similar ways and even make the exact same

behavioral mistakes we, ourselves, have condemned it’s fair to ask “what now?”

Is this it? Will this chapter be enough to raise questions without providing

much of an answer¬? Is everything always grey and in doubt? Is the rest of the

book more of the same which would make it no more than a superfluous addition

to this chapter required to provide what publishers call “spine value”?

Well, not quite. What follows are the elements, the modalities, if you like,

required to make this game of life work. What follows is the prescription you

need to live your life the way you want to. This chapter, however, is far from

over.

Because all this is serious I can afford to be flippant, though as you will

see even my flippancy has a very serious intent. So, I will add here that the

one ‘rule’ we all need to keep in mind is that favourite of William S.

Burroughs’ from his Naked Lunch “Nothing is true; everything is

permitted”. Burrough, of course, borrowed this from Vladimir Bartol, who used

it in his novel Alamut. Bartol, himself borrowed it, and slightly

changed it in the process, from the teachings of Hassan-i Sabbah who was the

founder of the Order of the Assassins, historically known as the Nizari

Assassins. The tale, writings and doctrine of the Order was incorporated in the

storyline of the popular video game Assassin’s Creed which is where I

first came across it and filed it away for future reference which brings us to

here and now. You reading what I’ve written.

What do we, what can we learn from this? That life is circuitous but the

circuit has polygonal junctures with cultural jumps and bends that require an

open mind and a thirst for cultural learning in order for the metaphorical dots

to connect? Or, that nothing is truly original, that everything is borrowed

from somewhere else and made to fit the moment and its time?

Both, I’d argue. If you are truly living and if you truly feel alive you are

aware of both context and history. Moment and time. Alamut was written

as an implied rebuke to Mussolini’s fascism. Naked Lunch is a

chronicle of the messiness of life and its often unplanned trajectory where the

brain makes sense of basically senseless moments of existence. This book is

about learning to behave in ways that help you get more out of your life.

Barnes &Noble → https://bit.ly/2YUNDxT

Target → https://bit.ly/2Z3sNfx

Powell's → https://bit.ly/3mVkfiU

David Amerland is a Chemical Engineer with an MSc. in quantum dynamics in laminar flow processes. He converted his knowledge of science and understanding of mathematics into a business writing career that’s helped him demystify, for his readers, the complexity of subjects such as search engine optimization (SEO), search marketing, social media, decision-making, communication and personal development. The diversity of the subjects is held together by the underlying fundamental of human behavior and the way this is expressed online and offline. Intentional: How to Live, Love, Work and Play Meaningfully is the latest addition to a thread that explores what to do in order to thrive. A lifelong martial arts practitioner, David Amerland is found punching and kicking sparring dummies and punch bags when he’s not behind his keyboard.

For More Information