Inside the Book:

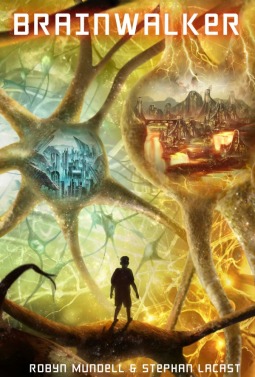

Title: Brainwalker

Author: Robyn Mundell & Stephan Lacast

Author: Robyn Mundell & Stephan Lacast

Release Date: September 26, 2016

Publisher: DualMind Publishing

Genre: Science Fiction

Format: Ebook/Paperback

And Bernard’s impulse control flies out the window when he’s stressed. So instead of turning in his project, he moons the class and gets suspended. Now his dad’s got no choice but to bring him to his work. At the Atom Smasher. It’s the chance of a lifetime for Bernard, who knows smashing atoms at the speed of light can—theoretically—make wormholes. How about that for the most mind-bending science project ever? But when he sneaks into the particle accelerator and someone hits the power button, Bernard ends up in the last place he’d ever want to be.

Inside his father’s brain.

And it’s nothing like the spongy grey mass Bernard studied at school. It’s a galaxy, infinite and alive. Like, people live there. A mysterious civilization on the brink of extinction, as unaware of their host as he is of them. But there’s zero time to process this. Bernard’s about to be caught up in an epic struggle between the two sides of his dad’s brain over their most precious resource:

Mental Energy.

With his father’s life at stake, Bernard must go up against the tyrannical left side of his father’s brain to save the dying, creative right side. But how the heck is he supposed to do that when he’s just a hopelessly right-brained kid himself?

Origins of the Myth of Right and Left Brained People

Everyone knows that right-brained people are more artistic and creative, while left-brained people are more logical and scientific. The only problem is that like many other things that “everyone knows,” this is a myth. It’s an attractive myth, it’s easy to explain and even easier to understand, but like many other such beliefs it is so much simpler than the truth that it’s utterly wrong. So why use this myth in the science-fantasy novel Brainwalker?

Like many other such ideas, this myth of brain “handedness” is a very old one. Nobody knows who first came up with the idea, but it goes back to at least the 1800s. As near as anyone can tell, it first took root when researchers noticed that patients with similar head injuries had similar problems. Specifically, they discovered that people with injuries in the left hemisphere developed language problems, while those with injuries in the right hemisphere were more likely to have problems with spatial knowledge.

The next leap forward came in the 1960s, when doctors started severing the corpus callosum as an epilepsy treatment. As scientists studied these patients, they discovered that they sometimes acted as if they had two completely different and separate minds. For example, a person might be asked a question and say one answer, but write another. This led to the theory of right or left brain dominance as demonstrated by Floyd and Bernard in the story.

Unfortunately, the brain didn’t follow the theory. Initially, scientists predicted that if one hemisphere was truly dominant, then it would be better developed. Artists would have more and stronger connections in the right brain, scientists in the left. The brain doesn’t work that way: it’s not so much the different areas that control things like creativity, but the connections. It is true that the left hemisphere controls the right side of the body, and the right hemisphere the left side, but that’s as far as it goes. Even when localized areas control specific functions, it’s not as cut and dried as the simple explanation would have it.

When it comes to thinking, both sides are in it together.

Getting back to the question of why we would use the idea in the science-fantasy Brainwalker, the basic answer is that it provides a basic conceptual framework for more important ideas. Yes, the fundamental idea that people are either left or right-brained is simplistic and inaccurate, but there really are creative people like Bernard, and analytical types like his father Floyd. Using the commonly understood terminology makes it easier for readers to follow the story. After all, most people have taken tests or been told they’re either left-brained or right-brained.

Besides, this kind of categorization isn’t all bad, either. If you can identify your own strengths and weaknesses, you know what to work on. The problem only comes in when you use these judgments as an excuse not to try.

Not trying is actually worse than it sounds because of the way the brain depends on connections. When you learn new things, you build new connections in the brain, and you can not only get better, but also rewire your brain to make things easier. You can actually see this in action by reading Brainwalker.

Floyd’s focus on logic and analytics is reflected in his brain, weakening the areas used for creative thought and strengthening those used for rote repetition. At the same time, Bernard is more focused on raw creativity until he is trapped in Floyd’s brain and forced to make use of his logical faculties. As Bernard travels through the Brainiverse, he builds new connections in his brain, strengthening his analytical abilities, or “left-brain.”

That is the real lesson of Brainwalker: that we aren’t locked into predetermined limits based on simplistic descriptions. Instead, we are all capable of forming new connections inside our brains and developing new skills and abilities. The human brain is malleable.

Meet the Authors:

French-Born Stephan Lacast likes to think of himself as a geek, which depending on your dictionary means either “knowledgeable about computers”, or “boring social misfit.” At the age of twelve his idea of fun was building computers and programming, and by fifteen he was a contributor to a computer magazine. A graduate of Paris-Dauphine University, he holds a Bachelor in Economics, a Master in Business Administration, and a Master of Advanced Studies in Information Systems. After teaching at Dauphine University, Stephan went on to work as a consultant and engineer for one of the top ten Information Technology services companies in Europe, before deciding to leave Paris and move to the United States.

Visit them at http://www.brainwalker.net